by T.D. Thornton

by T.D. Thornton

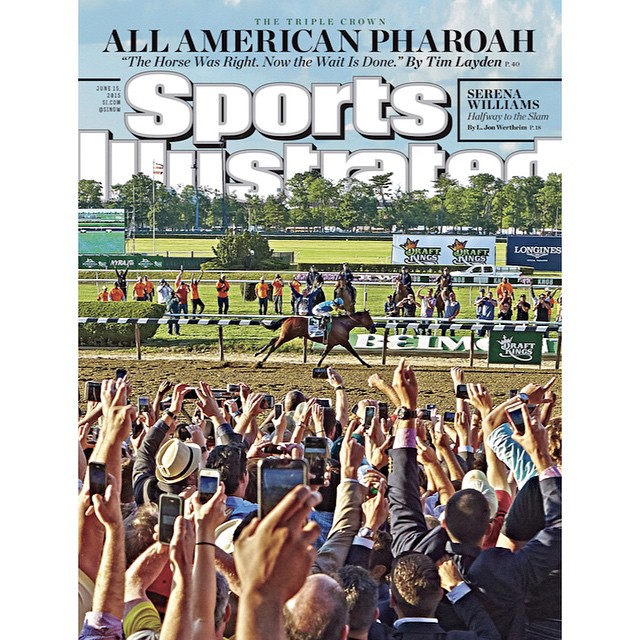

The cover of Sports Illustrated that commemorated American Pharoah (Pioneerof the Nile)'s Triple Crown victory captured not only the historical significance of the feat, but the uniquely 21st Century way the achievement was perceived by the public: The colt soaring toward the Belmont Park finish line occupied only a small section of the cover. The foreground was dominated by a legion of jubilant fans, smart phones straining aloft in a collective attempt to etch the experience in personal video and digital images.

Welcome to 2015, where simply witnessing history is no longer enough of a vicarious thrill, and seemingly everyone—both inside and outside the world of horse racing—feels the need to need to record, document, and in many cases, become a symbiotic part of live, real-time events as they unfold.

In terms of fan participation, American Pharoah's Triple Crown hardly resembles Secretariat's. In the 1970s, when the United States was graced with three Crown champs, telephones (both land lines and the drop-a-dime variety) were highly restricted at racetracks, and you couldn't have fathomed back then how by the next time a horse swept the G1 Kentucky Derby-Preakness-Belmont S., such devices would also be able to capture moving and still images.

In the 37-year gap between Crown winners, spectator passivity has been relegated to an anachronism. Now and moving forward, active participation and engagement are where it's at.

This technological revolution is affecting all sports worldwide. But you could make a pretty strong case that racing stands to benefit more than other sports by encouraging fan-made photos and videos and by incorporating such user-generated content (UGC) either alongside or, increasingly, as part of traditional reporting and broadcasts.

Racing already has an advantageous built-in participation component in the form of handicapping and wagering. And it's possible (in theory at least) for anyone to go from being a racetrack customer to a racehorse owner.

Yet racing clearly has a lot of catching up to do to when compared to the popularity of professional team sports in America. So getting passionate fans to engage in marketing at a miniscule cost to the industry would seem to be a no-brainer. As they say, word of mouth (or in this case, viral video from a smart phone) is the best advertising.

Earlier this month, Breeders' Cup Ltd. and the sport's main national television partner, NBC, took an enthusiastic leap into the realm of UGC by utilizing an emerging technological platform called Burst to infuse a significant degree of fan interactivity into the broadcast of the GI Stephen Foster Handicap at Churchill Downs.

In its simplest explanation, Burst allows a broadcaster to receive and sort through a massive number of real-time, fan-generated video streams. As the company's website explains, Burst expands traditional broadcast coverage “to unlimited perspectives from an army of smart phones,” culling them for both compelling content and technical quality to select clips that are best suited for broadcast.

“It goes from the phone into this 'bubble' that is controlled, in our case, by the Breeders' Cup,” said Peter Rotondo, the vice president for media and entertainment for the Breeders' Cup. “And then one click approves it for broadcast. So basically, in one fell swoop, it takes about a minute and a half to go from your iPhone to national television.”

Partnering with Burst, Rotondo said, will bring a whole new fan-involvement paradigm to racing broadcasts. But Burst is hardly the only UGC platform in the marketplace, and new technologies are being developed every day.

The important difference is that while Burst streamlines the job for conventional television broadcasters, competing technologies like the Twitter-based video streaming apps Periscope and Meerkat cut out the middleman entirely, putting no other entity between what a person wants to shoot with their smart phone and showing it in real time on the Internet.

This too, opens up exciting new possibilities for horse racing's exposure. But as other sports are learning, there are pitfalls and challenges to the concept of letting anyone, anywhere, stream moving and still images of live events as they happen.

“This is one of those disruptive events that folks have been predicting for a long time,” Karen Weaver, a professor of sports management at Drexel University, told the Boston Globe in a May 19 front-page story about how fan-streaming technologies are being perceived as threats. “It's another way for consumers to exercise their ability to see what they want to see.”

These live streaming technologies are so new that rights-holders (and networks that pay big bucks for the exclusive rights to broadcast premier events) aren't sure how to rein in unauthorized feeds. A scan of worldwide headlines over the past two months yields the following examples:

• Within the span of a week, the Professional Golfers' Association Tour went from barring a freelance reporter who used Periscope to interview a player during an off-limits practice round to promoting its own sanctioned Periscope stream.

• The Association of Tennis Professionals began threatening people with copyright infringement violations if they used unsanctioned images from matches for the purpose of “live GIFing” those events via social media.

• The National Hockey League sent a memo to teams emphasizing rules against journalists streaming pre- and post-game interviews, which it said conflicts with rights granted to television entities.

Spectators around the globe who paid $89.95 for the Floyd Mayweather Jr.-Manny Pacquiao boxing match flouted pay-per-view restrictions by pointing smart phones at television screens to send the fight to Periscope viewers. Certainly, the quality of the streamed feed was diminished, but it was free.

The Guardian reported May 16 that Formula One auto racing was “a little ahead of the game” with respect to other sports in cracking down on UGC: “If you read the fine print on the back of a ticket to a Formula One race, you'll find that anything you might video once you go through the turnstiles technically belongs to them. So if anyone is monetizing it, Formula One can go after the profits.”

Although journalists are streaming some of the Internet's sports-related UGC, much of it is uploaded by well-intentioned fans who are unaware that they might be infringing on someone's rights. In many instances within the realm of horse racing, there are no easily defined “rights” to begin with.

“People want that authentic point-of-view' footage out there of 'their' moments. It's the idea that their video could be famous, sort of their moment in the sun. At the Breeders' Cup, the crowds are so big that we want to really take people inside the event…It's 2015, this is what it's all about.”

–Peter Rotondo Predating the current explosion of streaming technology, a good promotional example of the use of UGC is the 23-minute harness racing documentary film “Race Day,” which was created in 2011 by editing together more than 10 hours of footage sent in by 20 volunteers across North America to tell the composite story of a typical day at the races.

Last week, a casual search of Twitter revealed Periscope streams (primarily paddock and live race footage) from the following U.S. racetracks: Arapahoe Park, Canterbury Park, Churchill Downs, Emerald Downs, and Indiana Grand. On June 18, you could have also watched a live stream of American Pharoah's arrival on the backstretch at Santa Anita Park. This was a happening that did not warrant live national broadcast coverage, but was sought out and watched by at least hundreds of racing fans who were alerted to it via Twitter.

Both Meerkat and Periscope are free to use, both for viewing and creating live streams. Meerkat does not currently have a function for saving replays of streams to be viewed later; Periscope streams vanish after 24 hours. The ability to archive replays of live streams is a feature that is expected to flourish as these and competing technologies evolve. Poor quality is the main drawback of UGC videos–they are often grainy, shaky or out of focus. But this too is expected to improve.

”I think it's something that should be encouraged,” said Jim Mulvihill, the director of media and industry relations for the National Thoroughbred Racing Association. “Anything that allows fans and the media new avenues for showing what goes on behind the scenes at the racetrack is probably a positive as long as it's used appropriately.”

But while America's smaller racetracks might welcome the live streaming exposure, there are bound to be entities higher up the totem pole that are wary of it.

Churchill Downs, Inc., for example, is widely known in the industry as a fierce protector of its Kentucky Derby brand, and CDI management is keeping a close eye on the new technology. “The growth of user-generated content is on our radar screen and is an issue we'll be assessing as we work toward the 2016 Kentucky Derby and Oaks,” said Ryan Jordan, Churchill Downs Racetrack General Manager, in an email reply to the TDN.

NBC, which owns the Triple Crown broadcasting rights, was asked in an email last Thursday how the network plans to simultaneously leverage the positive benefits of UGC while protecting itself against its pitfalls. NBC vice president of communications Dan Masonson acknowledged receipt of the query but did not provide a detailed reply prior to deadline for this story.

“I think if anybody was abusing it to try and circumvent rights-holders, it would be fairly obvious,” Mulvihill said, emphasizing that the NTRA does not have a “position” on the use of UGC one way or the other. “If somebody oversteps the bounds, it might only be because these technologies are so new and some of the boundaries are gray.”

Rotondo agreed: “I understand some of that. But for us, I think it's only going to help drive viewership to the larger broadcasts. Periscope is cool. We used it [recently] at Churchill. But it can only handle so many people to jump on the feed at once, and it's only that one singular view. It's almost like you get a taste of the event, and then you want to figure out where you can go to consume the whole thing.

“For [racing] it's different,” Rotondo continued. “You look at other sports. In the National Football League, what [is a fan with streaming capability] going to do? The user-generator, they're going to show the game, and it's the same play that all fans who are sitting there are going to see. I feel at the racetrack, when you have these big events, you have so many different things going on. You have the handicapping, the fashion, you've got the parties, the stretch run, the horses. There's more to absorb. Sometimes people don't realize that, and we're going to show it off.”

But another issue is that once the genie is out of the bottle, so to speak, it can't be reeled back in.

So if the racing industry actively encourages fans to document on-track experiences and share them with the world, it should be prepared for the inevitable tragic or less-than-feel-good moments that are only a click away from being widely distributed on the Internet.

In addition, there might be some live-streaming users whose intentions don't align with marketing the sport. An example of this is the clandestine backstretch footage compiled and released by the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals in 2014.

Mulvihill said in those sorts of instances, there is only so much the industry can do.

“Racing shouldn't be worried about the worst-case scenarios. We have so much to be proud and excited about, and we need these avenues to help our great sport reach new audiences,” Mulvihill said. “If there are worst-case scenarios that we spend too much time dwelling on, we'll miss the opportunities. All of these new technologies, there are certainly pitfalls to them. But they're here whether we love them or not, so we've got to find ways to use them to our advantage.”

To that end, Rotondo said he is eager to fine-tune the Burst interactivity in the NBC broadcasts. The Foster show was just the initial test of the technology.

“We're doing all this throughout the year, ultimately, to have it perfected Breeders' Cup weekend,” Rotondo said.

Currently, the Breeders' Cup has its own small staff of on-track reporters shooting smart-phone footage that gets uploaded into the Burst bubble. At the same time, the NBC broadcast posts a link for viewers to upload their own photos and videos.

“Whether it's how you're rooting your horse home, who you like in the race, you name it, we're getting it,” Rotondo said. “And you have to remember, it's not only people at the track, it's people anywhere.”

Rotondo explained that the Foster broadcast yielded 300 UGC submissions, but that he expects that number to grow as viewers become accustomed to participating.

“Obviously, the first time we did this, there weren't many people at home throwing Stephen Foster parties on a Saturday night. But when it comes to Breeders' Cup time, people do that,” Rotondo said. “That's the idea. By the time we get to the Breeders' Cup, we want content all week.”

Rotondo said his team learned a few things from the Foster broadcast. One was that night racing doesn't yield the best broadcast-quality shots. But quality issues were trumped by the sheer number of non-traditional smart phone camera angles, like one UGC clip that caught owner Ahmed Zayat lifting up jockey Victor Espinoza and embracing him in a bear hug during American Pharoah's between-races ceremony.

“We don't have enough cameras to be imbedded like that any other way,” Rotondo said.

“People want that authentic point-of-view' footage out there of 'their' moments,” Rotondo said. “It's the idea that their video could be famous, sort of their moment in the sun. I don't see any downside. At the Breeders' Cup, the crowds are so big that we want to really take people inside the event. And that view goes straight back to your point about the Sports Illustrated cover. It's 2015, this is what it's all about.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.